Understanding Policy Gradients

Table of Contents:

- Policy Gradients

- Geometric Intuition

- Math Background

- Policy Gradient Theorem

- The Probability of a Trajectory, Given a Policy

- The REINFORCE Algorithm

- TD Error as Advantage Function

- Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO)

- Truncated Natural Gradient Policy Algorithm

- PPO

Policy Gradients

Policy gradients is a reinforcement learning method, where an agent interacts with the world, taking decisions. After taking an action, the world (i.e. environment) changes, and this process repeats over and over and over.

We’ll examine the foundations of policy gradient methods – we’ll look at the basic derivation, then we’ll take advantage of temporal decomposition to be more data efficient then we’ll look at baseline subtraction, which will reduce the variance of our policy gradient method. Then we’ll look at the value and function estimation, which can further reduce variance. And then we’ll look at advantage estimation as a way to further improve our policy gradient method.

As opposed to Deep Q-Learning, policy gradients is a method to directly output probabilities of actions. We scale gradients of actions by reward.

Pros:

- A policy is often easier to approximate than value function. For example, if playing Pong, it is hard to assign a specific score to moving your paddle up vs. down.

- Policy Gradients works well empirically and was a key to AlphaGo’s success.

- Policy gradients learns stochastic optimal policies, which is crucial for many applications. For example, in the game of Rock, Paper, Scissors, a deterministic policy is easily exploited, but a uniform random policy is optimal.

- \(\pi\) simpler than \(V\): A value function doesn’t prescribe actions. If all we learn is a value function, we still don’t know what to do. You need maybe a dynamics model to do look ahead against the value of function, but then you also need to learn a dynamics model.

Cons:

- Training takes significant time. The use of sampled data is not efficient. High variance confounds actions. Need tons of data for estimator to be good enough.

- Converge to local optima. Often there are many optima.

- Unlike human learning: humans can use rapid, abstract model building.

Geometric Intuition

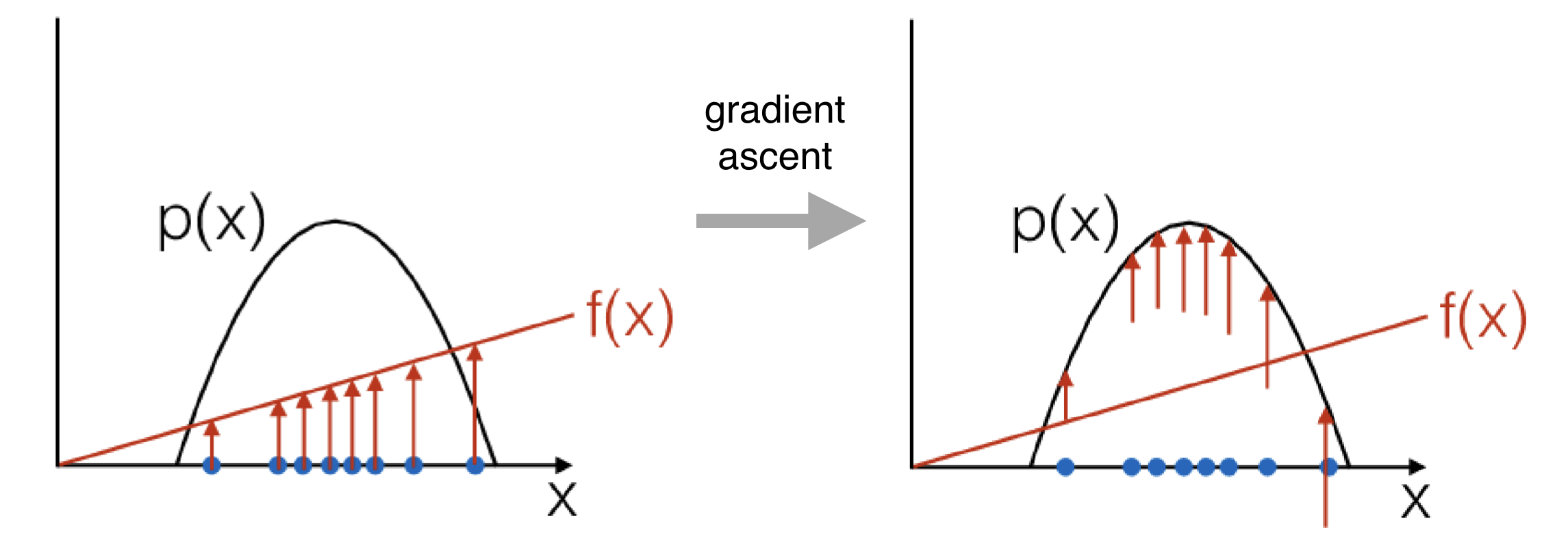

Suppose we have a function \(f(x)\), such that \(f(x) \geq 0 \forall x\) For every \(x_i\), the gradient estimator \( \hat{g}_i\) tries to push up on its density.

Math Background

To understand the proofs, you’ll need to understand 3 simple tricks:

- The derivative of the natural logarithm: \( \nabla_{\theta} \mbox{log }z = \frac{1}{z} \nabla_{\theta} z \)

- The definition of expectation:

- Multiplying a fraction’s numerator and denominator by some arbitrary, non-zero constant does not change the fraction’s value.

Policy Gradient Theorem

Let \(x\) be the action we will choose, \(s\) be the parameterization of our current state, \(\theta\) be the weights of our neural network. Then our neural network will directly output probabilities \(p(x \mid s; \theta)\) that depend upon the input (\(s\)) and the network weights (\( \theta \)).

We start with a desire to maximize our expected reward. Our reward function is \(r(x)\), which is dependent upon the action \(x\) that we take.

\[\begin{align} \nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p( x \mid s; \theta)} [r(x)] &= \nabla_{\theta} \sum_x p(x \mid s; \theta) r(x) & \text{Defn. of expectation} \\ & = \sum_x r(x) \nabla_{\theta} p(x \mid s; \theta) & \text{Push gradient inside sum} \\ & = \sum_x r(x) p(x \mid s; \theta) \frac{\nabla_{\theta} p(x \mid s; \theta)}{p(x \mid s; \theta)} & \text{Multiply and divide by } p(x \mid s; \theta) \\ & = \sum_x r(x) p(x \mid s; \theta) \nabla_{\theta} \log p(x \mid s; \theta) & \text{Apply } \nabla_{\theta} \log(z) = \frac{1}{z} \nabla_{\theta} z \\ & = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p( x \mid s; \theta)} [r(x) \nabla_{\theta} \log p(x \mid s; \theta) ] & \text{Definition of expectation} \end{align}\]A similar derivation can be found in (Sutton & Barto, 2017) or in (Schulman, 2016) or in (Abbeel, 2021).

What does this mean for us? It means that if you want to maximize your expected reward, you could do something like gradient ascent. It turns out that the gradient of the expected reward is simple to compute and analytical – it is simply the expectation of the reward times the log probabilities of actions.

Consider Trajectories

Now, let’s consider trajectories, which are sequences of actions.

The Markov Property states that Markov Property: the next state \(s^{\prime}\) depends on the current state \(s\) and the decision maker’s action \(a\). But given \(s\) and \(a\), it is conditionally independent of all previous states and actions.

The probability of a trajectory \(\tau\) (a state action sequence) is defined as:

\[p(\tau \mid \theta) = \underbrace{ \mu(s_0) }_{\text{initial state distribution}} \cdot \prod\limits_{t=0}^{T-1} \Big[ \underbrace{\pi (a_t \mid s_t, \theta)}_{\text{policy}} \cdot \underbrace{p(s_{t+1},r_t \mid s_t, a_t)}_{\text{transition fn.}} \Big]\]Before we had:

\[\nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p( x \mid s; \theta)} [r(x)] = \mathbb{E}_{x \sim p( x \mid s; \theta)} [r(x) \nabla_{\theta} \log p(x \mid s; \theta) ]\]Consider a stochastic generating process that gives us a trajectory of \((s,a,r)\) tuples:

\[\tau = (s_0, a_0, r_0, s_1, a_1, r_1, \dots, s_{T-1}, a_{T-1} r_{T-1}, s_T)\]We want the expected reward over a trajectory. The reason we want a sample-based approximation (expectation, weighted by probability), rather than a sum over all trajectories, is so that we can sample from the distribution to compute this thing. Then we don’t have to enumerate all possible trajectories, which would be completely impossible in realistic problems. We’re going to just take a sample based estimate.

\[\nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{\tau} [R(\tau)] = \mathbb{E}_{\tau} [ \underbrace{\nabla_{\theta} \log p(\tau \mid \theta)}_{\text{What is this?}} \underbrace{R(\tau)}_{\text{Reward of a trajectory}} ]\]The reward over a trajectory is simple: \(R(\tau) = \sum\limits_{t=0}^{T-1}r_t\)

In other words, it’s the sum of the rewards for each of the state action pairs. The expectation above can also be written as the sum over all possible trajectories we could encounter, the probability of experiencing that trajectory under the policy parameterized by \(\theta\), and then of course that’s what we weight the reward by. Our objective is

\[\underset{\theta}{\operatorname{arg max}} U(\theta) = \underset{\theta}{\operatorname{arg max}} \sum_\tau p(\tau \mid \theta) R(\tau)\]So every choice of our parameter vector \(\theta\) of our neural network will achieve a different expected sum of rewards when we use that policy. Our goal is to find a \(\theta\), the parameters in the neural network that will maximize \(U(\theta)\), which is a weighted sum of rewards associated with each possible trajectory \(\tau\) weighted by the probability of that trajectory. And by changing the parameters of the neural network, we’re changing the probability distribution over trajectories. Some settings will favor certain trajectories. Other settings will favor other trajectories. And so we want to find a setting of the parameters in the network, such that we favor the trajectories that have high reward and don’t favor the trajectories with lower rewards so much.

The Probability of a Trajectory, Given a Policy

Now, we’ll briefly consider a dynamics model (a transition function), but in the end we’ll see that now no dynamics model is required:

\[\begin{align} p(\tau \mid \theta) &= \underbrace{ \mu(s_0) }_{\text{initial state distribution}} \cdot \prod\limits_{t=0}^{T-1} \Big[ \underbrace{\pi (a_t \mid s_t, \theta)}_{\text{policy}} \cdot \underbrace{p(s_{t+1},r_t \mid s_t, a_t)}_{\text{transition fn.}} \Big] & \text{Markov Property} \\ \mbox{log } p(\tau \mid \theta) &= \mbox{log } \mu(s_0) + \mbox{log } \prod\limits_{t=0}^{T-1} \Big[ \pi (a_t \mid s_t, \theta) \cdot p(s_{t+1},r_t \mid s_t, a_t) \Big] & \text{Log of product = sum of logs} \\ &= \mbox{log } \mu(s_0) + \sum\limits_{t=0}^{T-1} \mbox{log }\Big[ \pi (a_t \mid s_t, \theta) \cdot p(s_{t+1},r_t \mid s_t, a_t) \Big] & \text{Log of product = sum of logs} \\ &= \mbox{log } \mu(s_0) + \sum\limits_{t=0}^{T-1} \Big[ \mbox{log }\pi (a_t \mid s_t, \theta) + \mbox{log } p(s_{t+1},r_t \mid s_t, a_t) \Big] & \text{Log of product = sum of logs} \\ \end{align}\]Maximizing Expected Return of a Trajectory

As we discussed earlier, in order to perform gradient ascent, we’ll need to be able to compute:

\[\nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{\tau} [R(\tau)] = \mathbb{E}_{\tau} [ \underbrace{\nabla_{\theta} \log p(\tau \mid \theta)}_{\text{Derived Above}} \underbrace{R(\tau)}_{\text{Reward of a trajectory}} ]\]We have just shown that the inner term is simply:

\[\log p(\tau \mid \theta) = \mbox{log } \mu(s_0) + \sum\limits_{t=0}^{T-1} \Big[ \mbox{log }\pi (a_t \mid s_t, \theta) + \mbox{log } p(s_{t+1},r_t \mid s_t, a_t) \Big]\]We need its gradient. Only one term depends upon \(\theta\) above, so all other terms fall out in the gradient:

\[\nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_{\tau} [R(\tau)] = \mathbb{E}_{\tau} \Big[ R(\tau) \nabla_{\theta} \sum\limits_{t=0}^{T-1} \mbox{log }\pi (a_t \mid s_t, \theta) \Big]\]Now what’s interesting when you look at this is that this can be used no matter what our reward function is. We don’t need to be able to take a derivative of our reward function for this to work, the only derivatives taken are with respect to the neural network, i.e. with respect to the distribution of our trajectories, which is induced by the neural network that encodes our policy, we don’t need a gradient with respect to the reward function. And so you can have a reward function that is for example, one when you achieve the goal, zero everywhere else, and this will work.

When we look at this gradient here, we collected some trajectories, we look at the grad log probability trajectories and the reward. If the trajectory has very high reward, then the log probability of that trajectory will be increased. So trajectories with high reward will get an increase in their probability. If now we have a trajectory with a very negative reward we’ll move the parameter vector theta by moving in the gradient direction to decrease the probability of that trajectory. We’re pushing up for rewards that are positive high and pushing down the probability for trajectories, uh, where the reward was negative low. Effectively, shift probability mass away from trajectories with bad rewards, and shift probability mass towards trajectories with high reward.

It’s a bit more subtle than that because probabilities have to integrate to one. And so by pushing probability up in some places you’re implicitly also pushing it down in other places and the other way around.

This concludes the derivation of the Policy Gradient Theorem for entire trajectories.

The REINFORCE Algorithm

The REINFORCE algorithm is a Monte-Carlo Policy-Gradient Method. Below we describe the episodic version:

- Input: a differentiable policy parameterization \(\pi(a \mid s, \theta)\)

- Initialize policy parameter \(\theta \in \mathbb{R}^d\)

- Repeat forever:

- Generate an episode \(S_0\), \(A_0\), \(R_1\), … , \(S_{T−1}\), \(A_{T−1}\), \(R_T\) , following \( \pi(\cdot \mid \cdot, \theta) \)

- For each step of the episode \(t = 0, … , T-1\):

- \(G \leftarrow\) return from step \(t\)

- \( \theta \leftarrow \theta + \alpha \gamma^t G \nabla_{\theta} \mbox{ ln }\pi(A_t \mid S_t, \theta) \)

See page 271 of [1] for more details. Andrej Karpathy has a very simple 130-line script here that illustrates this in Python.

REINFORCE With a Baseline

In the section on geometric intuition, we discussed how: Suppose we have a function \(f(x)\), such that \(f(x) \geq 0 \forall x\) For every \(x_i\), the gradient estimator \( \hat{g}_i\) tries to push up on its density.

However, we really want to only push up on the density for better-than-average \(x_i\):

\[\begin{align} \nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_x [f(x)] &= \nabla_{\theta} \mathbb{E}_x [f(x) -b] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_x \Big[ \nabla_{\theta} \mbox{log } p(x \mid \theta) (f(x) -b) \Big] \end{align}\]A near optimal choice of baseline \(b\) is always the mean return, \( \mathbb{E}[f(x)]\).

Actor Critic

Monte Carlo Policy Gradient has high variance. What if we used a critic to estimate the action-value function?

\[Q_w(s,a) \approx Q^{\pi_\theta}(s,a)\]The Actor contains the policy and is the agent that makes decisions. The Critic makes no decisions or actions, but merely watches what the critic does and evaluates if it was good or bad.

Actor-Critic with Approximate Policy Gradient

The critic says, “Hey, I think if you go in this direction, you can actually do better!”

In each step, move a little bit in the direction that the critic says is good or bad.

Advantage Function

We remember the state-value function \(V^{\pi}(s)\), which tells us the goodness of a state. We remember the state-action function \(Q(s,a)\).

We want an advantage function \(A^{\pi}(s,a)\) to tell us how much better is action \(a\) than what the policy \(\pi\) would have done otherwise:

Did things get better after one time step? Of course, a Critic could estimate both. But there’s a better way!

TD Error as Advantage Function

Make the good trajectories more probable, make the bad trajectories less probable (high variance)

Monte Carlo

- unbiased but high variance

- conflates actions over whole trajectory

TD Learning

- introduces bias (treating guess as truth) but estimate have lower variance

- incorporates 1 step

- usually more efficient

For the true value function \(V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s)\), the TD error \( \delta^{\pi_{\theta}}(s)\)

\[\delta^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) = r + \gamma V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s^{\prime}) - V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s)\]is an unbiased estimate of the advantage function.

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \Big[\delta^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \mid s,a \Big] &= \mathbb{E}_{\pi_{\theta}} \Big[ r + \gamma V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s^{\prime}) - V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \Big] \\ = Q^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) - V^{\pi_{\theta}}(s) \\ = A^{\pi_{\theta}}(s,a) \end{aligned}\]TRPO: From 1st Order to 2nd Order

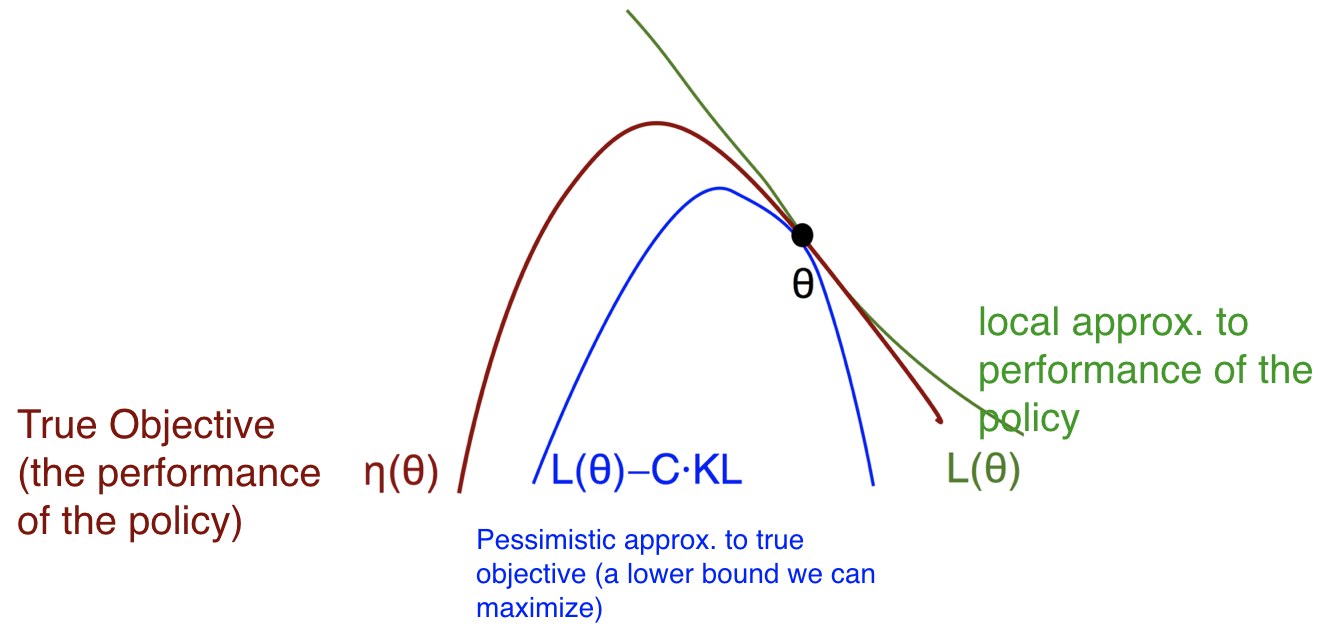

We don’t have access to the objective function in analytic form. However, we can estimate the gradient as the expected return of our policy by sampling trajectories. The gradient ascent update is correct if we make an infinitesimally small change.

A local approximation is only accurate closeby:

Trust-region methods penalize large steps. Let’s call our surrogate objective \(L_{\pi_{old}}(\pi)\). Let’s call our true objective \( \eta(\pi)\). We will add a penalty for moving \( \theta \) from \( \theta_{old} \) (KL Divergence between the old and new policy).

\[\eta(\pi) \geq L_{\pi_{old}}(\pi) - C \cdot \max\limits_s KL \Big[ \pi_{old}(\cdot \mid s), \pi(\cdot \mid s) \Big]\]Monotonic improvement will be guaranteed.Since the max is not good for Monte Carlo estimation, a practical approximation is:

\[\eta(\pi) \geq L_{\pi_{old}}(\pi) - C \cdot \mathbb{E}_{s\sim p_{old}} KL \Big[ \pi_{old}(\cdot \mid s), \pi(\cdot \mid s) \Big]\]Second Order Optimization Method

What if we used a 2nd order optimization method instead of our vanilla 1st order optimization method? We would compute the Hessian of the KL divergence, not of our objective

Hessian computation is extremely expensive…( 100,000 x 100,000 )

Truncated Natural Gradient Policy Algorithm

- for iteration 1,2,.. do

- Run policy for \(T\) timesteps or \(N\) trajectories

- Estimate advantage function at all timesteps

- Compute policy gradient \(g\)

- Use Conjugate Gradient (with Hessian-vector products) to compute \( H^{-1}g \)

- Update policy parameter \( \theta = \theta_{old} + \alpha H^{-1}g \)

Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO)

The Truncated Natural Policy Gradient algorithm was an unconstrained problem:

\[\eta(\pi) \geq L_{\pi_{old}}(\pi) - C \cdot \mathbb{E}_{s\sim p_{old}} KL \Big[ \pi_{old}(\cdot \mid s), \pi(\cdot \mid s) \Big]\]TRPO is a constrained problem (otherwise, algorithm is identical):

\[\begin{aligned} \mbox{max } & L_{\pi_{old}}(\pi) \\ \mbox{subject to } & \mathbb{E}_{s\sim p_{old}} KL \Big[ \pi_{old}(\cdot \mid s), \pi(\cdot \mid s) \Big] \leq \delta \end{aligned}\]The constraint is accomplished through a KL term, but the formulation requires a second-order aspect.

Easier to set hyper parameter \(\delta\) rather than \(C\). \(\delta\) can remain fixed over whole learning process… Simply rescale step by some scalar.

\[\begin{aligned} U(\theta) &= \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \theta_{\text{old}}} \left[ \frac{P(\tau|\theta)}{P(\tau|\theta_{\text{old}})} R(\tau) \right] \\ \\ \nabla_\theta U(\theta) &= \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \theta_{\text{old}}} \left[ \frac{\nabla_\theta P(\tau|\theta)}{P(\tau|\theta_{\text{old}})} R(\tau) \right] \\ \\ \nabla_\theta U(\theta) \big|_{\theta = \theta_{\text{old}}} &= \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \theta_{\text{old}}} \left[ \frac{\nabla_\theta P(\tau|\theta) \big|_{\theta = \theta_{\text{old}}}}{P(\tau|\theta_{\text{old}})} R(\tau) \right] \\ \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \theta_{\text{old}}} \left[ \nabla_\theta \log P(\tau|\theta) \big|_{\theta = \theta_{\text{old}}} R(\tau) \right] \end{aligned}\]KL Evaluation

To evaluate the KL, we recall that \(P(\tau; \theta) = P(s_0) \prod_{t=0}^{H-1} \pi_\theta(u_t | s_t) P(s_{t+1} | s_t, u_t)\): \(\begin{aligned} \\ \\ \text{Hence:} \quad KL(P(\tau; \theta) \| P(\tau; \theta + \delta \theta)) &= \sum_{\tau} P(\tau; \theta) \log \frac{P(\tau; \theta)}{P(\tau; \theta + \delta \theta)} \\ &= \sum_{\tau} P(\tau; \theta) \log \frac{P(s_0) \prod_{t=0}^{H-1} \pi_\theta(u_t | s_t) P(s_{t+1} | s_t, u_t)}{P(s_0) \prod_{t=0}^{H-1} \pi_{\theta + \delta \theta}(u_t | s_t) P(s_{t+1} | s_t, u_t)} \\ &= \sum_{\tau} P(\tau; \theta) \log \frac{\prod_{t=0}^{H-1} \pi_\theta(u_t | s_t)}{\prod_{t=0}^{H-1} \pi_{\theta + \delta \theta}(u_t | s_t)} \\ &\approx \frac{1}{M} \sum_{(s,u) \text{ in roll-outs under } \theta} \log \frac{\pi_\theta(u|s)}{\pi_{\theta + \delta \theta}(u|s)} \end{aligned}\)

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)

Compared to TRPO, PPO instead has only a first-order aspect to it. We move from the TRPO objective:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{maximize}_{\theta} \quad & \hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t \mid s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t \mid s_t)} \hat{A}_t \right] \\ \text{subject to} \quad & \hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \mathrm{KL}[\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot \mid s_t), \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid s_t)] \right] \leq \delta \end{aligned}\]to the PPO objective:

\[\begin{aligned} \max_{\theta} \; \hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t \mid s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t \mid s_t)} \hat{A}_t \right] - \beta \left( \hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \mathrm{KL}\left[\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(\cdot \mid s_t), \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid s_t)\right] \right] - \delta \right) \end{aligned}\]Pseudocode:

for iteration=1,2,… do

- Run policy for T timesteps or N trajectories

- Estimate advantage function at all timesteps

- Do SGD on above objective for some number of epochs

- Do dual descent update for beta

PPO v2 uses a “Clipped Surrogate Loss”. Let:

\[\begin{aligned} r_t(\theta) = \frac{\pi_\theta(a_t \mid s_t)}{\pi_{\theta_{\text{old}}}(a_t \mid s_t)}, \quad \text{so} \quad r(\theta_{\text{old}}) = 1 \end{aligned}\]We optimize:

\[\begin{aligned} L^{\text{CLIP}}(\theta) = \hat{\mathbb{E}}_t \left[ \min\Bigg( r_t(\theta) \hat{A}_t, \, \text{clip}\big(r_t(\theta), 1 - \epsilon, 1 + \epsilon\big) \hat{A}_t \Bigg) \right] \end{aligned}\]Baseline Subtraction

Above, we’ve shown how to compute on expection the correct policy gradient, but it’s very noisy. It’s sample based. And if you don’t have enough samples, not going to be very precise,

One fix that will lead to real-world practicality is the notion of a baseline. Our intuition was that we’re going to increase the probabilities of trajectories with high award, decrease probability of trajectories with low reward.

But actually really we want something a little more subtle, right? What we really want is we want to increase the log probability of trajectories that are above average, and decrease the probability of trajectories that are below average. Because if something’s below average, you want to do less of it as above average, we want to do more of it. But here, if for example, you have an MDP where the rewards are always positive for every state. The rewards are, let’s say between zero and one, then no matter what you experienced, you’re always going to have a contribution here that says let’s increase the law of probability of what I did.

What we’d really prefer is to shift our probabilities in a better way. Something called baseline subtraction will get us what we want. Now consider introducing a baseline b. Just going to subtract something out.

Then things that are above average will have an increase in their log probability of action given state and the ones below baseline will have a decrease in their probability of action given state and accordingly trajectories.

Can we do this? Is it still an okay, gradient estimate? Well, what you’ll see is that on expectation, this extra term will be zero. It’s a very interesting why we even care about it, why are we adding this minus b if an expectation it’s a zero contribution?

Well, on expectation it is. But when there’s finite samples, the estimate we’re accumulating here, it will actually have a reduction of variance effect, you’ll get a better gradient estimate.

References:

[1] Richard Sutton and Andrew Barto. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. Chapter 13. http://incompleteideas.net/book/bookdraft2017nov5.pdf.

[2] John Schulman. Deep Reinforcement Learning: Policy Gradients and Q-Learning.Bay Area Deep Learning School, September 24, 2016. [PDF]

[3] Andrej Karpathy. Deep Reinforcement Learning: Pong from Pixels. May 31, 2016. http://karpathy.github.io/2016/05/31/rl/.

[4] L4 TRPO and PPO (Foundations of Deep RL Series). Pieter Abbeel. YouTube.

[5] L3 Policy Gradients and Advantage Estimation (Foundations of Deep RL Series). Pieter Abbeel. YouTube.